…though not asked to Dance, per se…

The Gun Moll’s successor, USS Chicago (CA-136), was invited. To Tokyo Bay for the formal, the formal surrender of Imperial Japan to the Allied Powers that is. She and the three other heavy cruisers in Cruiser Division 10, USS Boston (CA-69), USS Quincy (CA-71, division flagship) and USS St. Paul (CA-73) were four units of the powerful Baltimore-class of heavy cruisers joining in. They were among the numerous Allies vessels present at the formal surrender and the start of the Allied occupation of Imperial Japan 75 years ago.

Chicago was part of Task Force 35 (TF 35), a mixed cruiser /destroyer force that included battleship USS South Dakota (BB-57) and light carrier USS Cowpens (CVL-25) with the mission of making a demonstration of force in Sagami Wan (which leads to Tokyo Wan, aka Tokyo Bay) and to reinforce, support and cover other task forces and groups in the area when directed. TF 35 included CruDiv 10’s four heavy cruisers, four light cruisers, 17 destroyers, four destroyer escorts, a dozen auxiliaries (including four hospital ships for liberated prisoners of war) and an LST, per Annex “A” to ComThirdFlt Op Plan No. 10-45.

Chicago and her task force approached Honshu on 26 August in accordance with Op Order 10-45 and at 0330 on Monday, 27 August commenced her approach with other vessels in accordance with ComThirdFlt entrance Plan #1 of August 1945. During the morning Chicago was one of a dozen of ships in the formation that received mail from destroyer USS Knapp (DD-653).

At 0813 on 27 August lookouts on Chicago sighted Hu Shima (Oshima?) bearing 243 degrees (True) By afternoon she reached Sagami Wan and at 1425 dropped anchor at Berth #8 in 16-½ fathoms of water in an anchorage in the northeast part of the bay. From Berth #8 she took the following bearings to Eno Shima (left tangent) 029-1/2 degrees (T), Eno Shima (right tangent) 048 degrees (T), Imemuragi Saki (right tangent) 073-3/4 degrees (T), and Ubaga Shima 291 degrees (T).

Sister-ship Boston’s war diary added some interesting details about this arrival after she dropped anchor at Berth #7, the center of which bore 175 (T), about 1800 yards from the western end of Eno Shima: “Entry was made almost entirely devoid of incident. Several floating mines were sighted but all were avoided… Nothing of importance took place the rest of the afternoon or night. Some Japanese civilians were sighted engaging in fishing activity off the eastern tip of ENO SHIMA but appeared to be incurious concerning the Fleet. No attempts to approach the ships were made.”

Having arrived in Japanese waters, there were certain precautions directed by the TF 35 commander. Destroyer patrols and armed small boat pickets protected the anchorage from any prospective suicide craft. Again, Boston’s war diary details some of this: “SOPA (Senior Officer Present Afloat in a harbor with more than one US Navy vessel present) SAGAMI WAN (CTF 35) directed that condition of readiness I-Easy in the anti-aircraft batteries be maintained from sunrise to sunset with condition I-AA being set an hour before sunrise and for an hour after sunset. Condition III was maintained through the night. Material condition Zebra, modified, was maintained at all times. Engineering plant was kept in readiness to get underway with half-boiler power at a moment’s notice and an anchor watch ready to slip the anchor was stationed at all times. A small-boat picket patrol was maintained continuously around the anchorage, with BOSTON, designated guard ship for the patrol from ENO SHIMA eastward for three miles, Motor whale boats from BOSTON, QUINCY, and CHICAGO patrolled area in rotation.”

Chicago remained anchored on 28 August in the same position. Sister-ship St. Paul also contributed to the patrol effort, as her war diary reported a significant development in that morning, when at 0900 the ship’s No. 2 motor whaleboat, Ensign George A. Bentley in charge and on picket boat duty west of Eno Shima, rescued two escaped prisoners of war who swam out to them from Eno Shima. John W. Wynn, British Royal Marines, and Edgar Tombell (USS San Juan war diary reports name as Pvt. E. D. Campbell), British Army Service Corps, had been captured at Hong Kong on 25 December 1941. They were subsequently taken at 1030 to US light cruiser San Juan, the command ship of the specially- constituted Allied Prisoner of War Rescue Group and in the afternoon transferred to CTF 111.

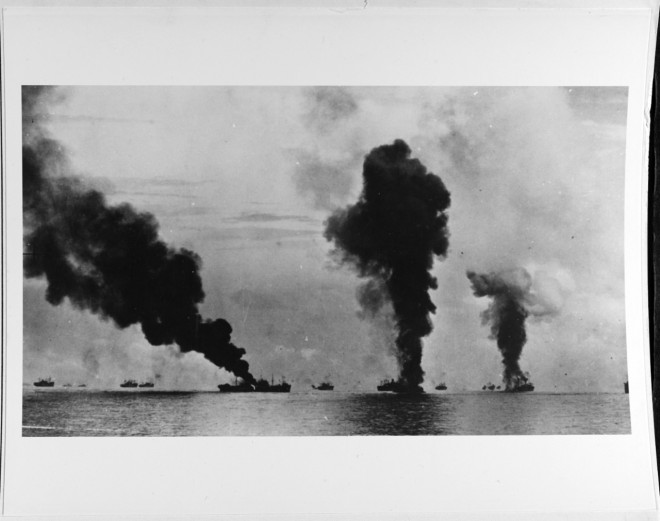

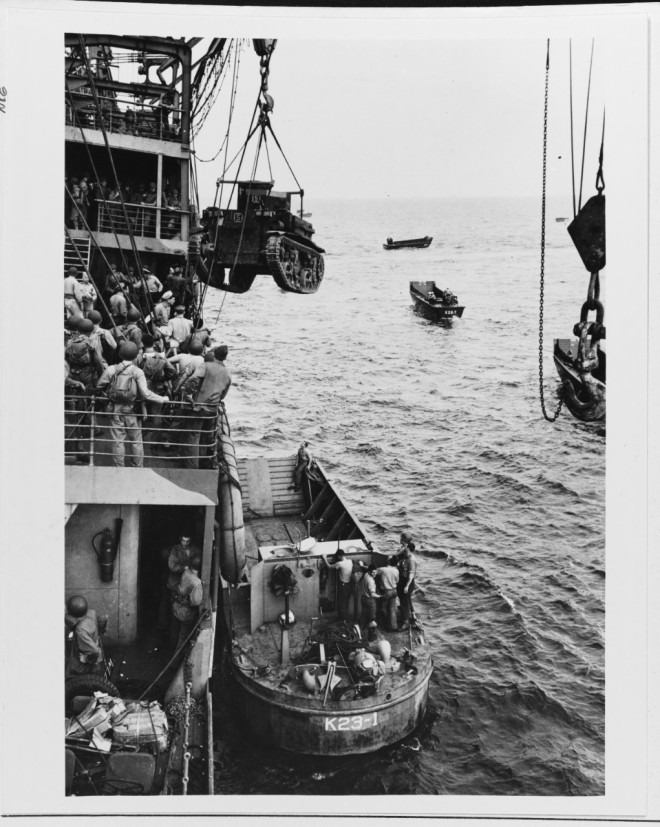

The former POW’s described their camp life and the poor condition many of the prisoners were in – reported up the chain of command, this information prompted Admiral Halsey to order the POW rescue group to move forward into Tokyo Bay and commence recovery operations. By 1910 on the evening of 29 August the first recovered POWs were aboard hospital ship USS Benevolence (AH-13); by midnight 739 men had been liberated from camps in the area.

Also on 28 August, Third Fleet ships discontinued the practice of darkening ship at night. Per the Third Fleet War Diary “Ships showed standard anchor lights, gangway lights, and help movies topside. Ships underway showed dimmed running lights. All ships were prepared to darken immediately should an emergency so require.” Thankfully, there were no incidents.

On 29 August Chicago got underway at 0634 to fuel from USS Neches (AO-47). She completed her fueling by 0829, got underway again and returned to the anchorage. She dropped anchor at 0900 back at Berth #8. Neches was the first oiler to enter Tokyo Bay and served as a station tanker that fueled 120 ships between 29 August and the end of September 1945.

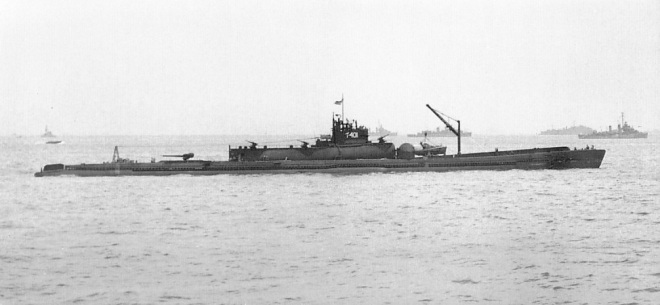

Sister ship Quincy’s war diary reported an unusual sight on this 29th day, when two Japanese submarines, surrendered and now manned by American prize crews, stood into the area. The Third Fleet war diary reports that Japanese subs I-400 and I-14 moored alongside submarine tender USS Proteus (AS-19) in Sagami Wan at 0930 that day. Of note the I-400 was the first of a class of three seaplane-carrying submarines that were the largest submarines of World War II and for many years afterward.

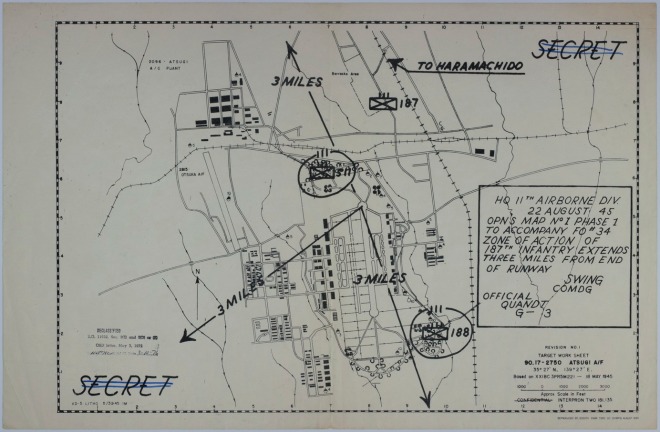

The next day, 30 August, Chicago got underway at 0525 IAW ComCruDivTEN dispatch 291035 Aug 1945 to take up a fire support position IAW Para. 2A of Annex A, ComCruDivTEN Op Order 4-45, 291035 of August, 1945. The war diary for USS Knapp reports the four heavy cruisers of CruDiv 10, light cruisers USS Wilkes-Barre (CL-103) and USS Springfield (CL-66), along with Knapp and other destroyers in Destroyer Division 100, covered the airborne landings that day as C-54 transport aircraft carried 4,200 paratroopers of the 11th Airborne Division from Okinawa to Atsugi Airfield in order “…to secure the surrounding area, evacuate all Japanese civilians and military personnel within a radius of three miles (4.8 km), and finally occupy Yokohama itself.” (11th Airborne Division, Wikipedia)

Boston’s war diary stated that “…at about 0600, large flights of transport aircraft and bombers escorted by Army and Navy fighters commenced passing overhead as air movement of troops to ATSUGI Airfield began.” Boston employed two floatplanes, one launched to relieve the other after a time, as spotter aircraft if naval gunfire support for the airborne troops inland was required, but it was not. Quincy’s war diary reports her standby fire support position was in Sagami Wan, seven miles south of the anchorage at the near Eno Shima. The cruisers were arranged in a north-south line and she also launched two floatplanes in succession for spotter duty. It’s reasonable to assume that Chicago also employed her Curtis SC-1 Seahawk floatplanes in support of her assigned station or sector. Quincy’s diary commented “All news received throughout the day indicated a orderly, bloodless occupation. No need for active fire support at any time.”

Of note, amphibious landings of Allied troops, Marines and sailors, also took place this day at forts guarding the entrance to Tokyo Bay and at Yokosuka Naval Base. St. Paul’s war diary for 30 August indicates she supported the landings by US occupation forces at Yokosuka Naval Base and used one of her floatplanes as a spotter over her assigned target area. So aside from destroyer Knapp’s reference to specific ships involved in supporting the airborne landings it’s a bit unclear to the writer of this web log if Chicago supported the airborne landing at Atsugi Airfield from within Sagami Bay, or the amphibious landings at Yokosuka just inside Tokyo Bay, or maybe even both depending on the position of the vessel.

Chicago reached her station (unidentified in her war diary) at 0611 and patrolled on various courses at various speeds in the fire support area. Things remained calm and quiet and at 1650 Chicago commenced her return to the now familiar Berth #8 and anchored at 1718. There she stayed in Sagami Wan on 1 September.

Chicago noted in her War Diary on 1 September that she was anchored at Berth #8, that the OTC and CTG 35.1 (Rear Admiral J.C. Jones, Jr., USN) was embarked aboard USS Pasadena (CL-65) and that ComThirdFleet (Admiral William F. Halsey, USN) was embarked in USS Missouri (BB-63), anchored in Tokyo Bay.

It is apparent to the writer of this web log that although many Allied ships were “present” for the surrender on 2 September 1945, not all were actually in Tokyo Bay in proximity to USS Missouri. Indeed, it appears that Allied ships were anchored in Tokyo Bay, in Sagami Wan, at Yokosuka naval base, and on patrol in waters nearby. There is yet to be produced any kind of chart showing the anchored positions of the long list of Allied ships on 2 September 1945 during the surrender ceremony. See the long list of vessels at: https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/a/allied-ships-present-in-tokyo-bay.html

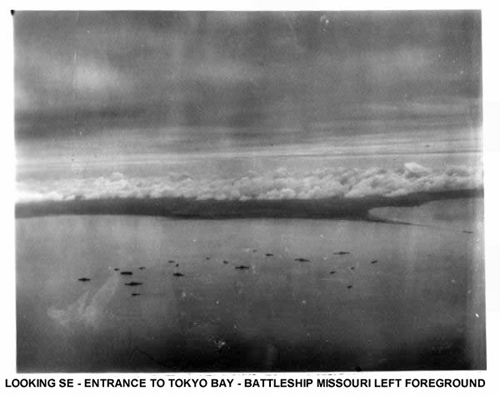

There may not be a chart but there are some clues about the disposition of the ships that day, like the war diaries of individual ships. There are also images such as this undated photo taken from a B-29 Superfortress of a gathering of approximately 20 ships in Tokyo Bay, with USS Missouri identified at the lower left. The prominent finger of land jutting into the water in the center right is likely Futtsu Misaki on the east side of Tokyo Bay.

And there is a nifty little chart of the Royal Navy light cruiser HMS Newfoundland that shows a berthing area for vessels in Sagami Wan and another in Tokyo Wan. The source says US and RN heavy units left Sagami Wan on 30 August and proceeded into Tokyo Bay, leaving behind a dozen ships in Sagami Wan, though various ships’ war diaries reflect daily movement of ships back and forth between the two bays.

HMS Newfoundland, HMNZS Gambia and an unidentified force of US cruisers proceeded to Tokyo Bay on 31 August. The British source also notes “Defense measures here include a pom-pom each side manned during daylight hours and a full cruising watch & lookout closed up at night, Sentries are posted from sunset to ‘hands fall in’.

USS Boston’s war diary on 1 September reported that two sisters of CruDiv 10, Quincy and St. Paul, departed Sagami Wan with battleships USS Mississippi (BB-41) and USS Colorado (BB-45) and proceeded into Tokyo Bay with some other ships. Boston and Chicago stayed in Sagami Wan.

Chicago’s entry for 2 September, the day of the formal signing of Imperial Japan’s surrender aboard Missouri, only says “Anchored as before” in Sagami Wan. Though surely the officers and men knew about the proceedings aboard Missouri that took place shortly after 0900 Tokyo time:

Chicago’s crew also surely witnessed the approach and overflight of 450 naval aircraft launched from fleet carriers east of Japan and then some 500 B-29s from the Marianas flying over the area after the ceremony.

Chicago did transit from Sagami Wan to Tokyo Bay on 3 September and was in company with Missouri and other ships that were present at the surrender ceremony the day before. She got underway at 0754 and Boston’s war diary reports that Chicago was the first ship in a column to enter Tokyo Bay that day, with the order as follows: Chicago, Boston, Springfield, Wilkes-Barre, and battleships USS Idaho (BB-42) and USS New Mexico (BB-40). Boston herself entered Tokyo Bay waters by 0947. At 1200 Chicago anchored in Berth C-74 in 17 fathoms of water. Boston dropped anchor at Berth C-73 in Tokyo Bay. Chicago remained in Tokyo Bay through the end of the month, shifting to Berth F-45 on 9 September as the occupation of Japan proceeded.

This web log writer has been aboard the Iowa-class battleship USS Missouri (BB-63) with family, both when she was in reserve at Bremerton, Washington as well as years later in museum status in Pearl Harbor, a solemn sight with the remains of battleship USS Arizona (BB-39) nearby.

It’s also interesting to the writer of this web log that the Fletcher-class destroyer USS Knapp (DD-653) was part of Task Force 35 and also present in Tokyo Bay on September 2, anchored at Berth C-6 after serving on picket duty in Sagami Wan as part of Destroyer Division 100 the day before. The author went aboard the preserved bridge section of USS Knapp with a shipmate in 2018 at its present location in the Columbia Maritime Museum in Astoria, Oregon. Although it’s unclear of the proximity of USS Knapp to USS Missouri insofar as the surrender ceremony goes, they were in Tokyo Bay proper that day. And USS Chicago joined them the next day.

For USS Chicago (CA-136) today, however, little remains, aside from an anchor for the ship that was saved when the ship was scrapped and later installed as a memorial display in 1995 on Navy Pier in Chicago. Perhaps this anchor was used to moor the ship at Sagami Wan and in Tokyo Bay in August and September of 1945? And thus in a way like USS Missouri and the bridge of USS Knapp is an artifact from the formal surrender of Imperial Japan.

But for the purpose of this web log it’s worth noting that USS Chicago (CA-136) was part of the Allied armada present in the greater Tokyo Bay area for the formal surrender of Imperial Japan. That is a fact of significance in the ship’s history. And the waters of the Japanese Home Islands were an appropriate place to remember the service and sacrifice of her predecessor and crew, the Gun Moll of the Pacific, USS Chicago (CA-29) some 31 months before which helped make that victory possible.

References

USS Chicago (CA-136), War Diaries for August and September 1945

Image of Chicago off Philadelphia Navy Yard, at: http://www.historyofwar.org/Pictures/pictures_USS_Chicago_CA136_1945.html

Third Fleet War Diary, August 1945

War Diaries for USS Boston, Quincy, St. Paul, Knapp, San Juan, Aug-Sep 1945

Report of Operations of the Third Fleet 16 August 1945 to 19 September 1945

Allied Ships Present in Tokyo Bay During the Surrender Ceremony, 2 September 1945, at: https://www.history.navy.mil/research/library/online-reading-room/title-list-alphabetically/a/allied-ships-present-in-tokyo-bay.html

USS Neches (AO-47), Wikipedia entry at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/USS_Neches_(AO-47)

HMS Newfoundland map and info at: https://wjdrnzns519.wordpress.com/2017/08/31/august-31-fri-1945-tokyo-bay-japan/

USS Boston at Tokyo Bay, at: http://www.ussboston.org/tokyobay.html

I-400-class submarine, Wikipedia entry at: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/I-400-class_submarine

1:32 26′ Motor Whaleboat Rescue Scene, at: http://steelnavy.com/gallery_dioramas.htm

Smith, Charles R., Securing the Surrender: Marines in the Occupation of Japan, at: http://npshistory.com/publications/wapa/npswapa/extContent/usmc/pcn-190-003143-00/sec1.htm

MacArthur Reports, Volume 1 Supplement, Chapter II, Troop Movements, Dispositions, and Locations, at: https://history.army.mil/books/wwii/MacArthur%20Reports/MacArthur%20V1%20Sup/ch2.htm

Map of 11th Airborne Division at Atsugi Airfield, at: https://www.trumanlibrary.gov/maps/m651-map-11th-airborne-division-atsugi-airfield