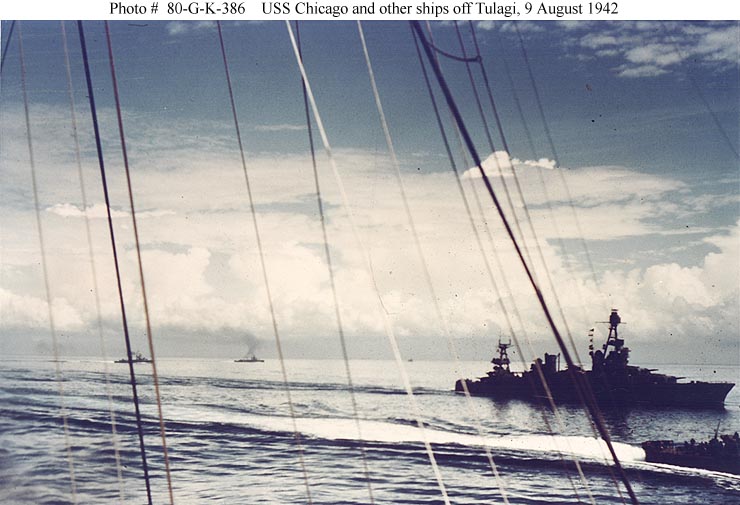

Life can sometimes present us with a defining moment. As the captain of the US Navy heavy cruiser USS Chicago (CA-29), Howard D. Bode faced such a time in the early morning hours of August 9, 1942 at the Battle of Savo Island.

There at the ignominious battle he was presented with the opportunity to distinguish himself in battle as a hero, or as a goat (not to be confused with the modern acronym Greatest Of All Time). He received a surprising, “golden opportunity” to demonstrate his skill and prowess as the commander of a US Navy fighting ship. He was at the pinnacle of his naval career, or perhaps better described as the apex of it, in the moments before this battle began, eighty years ago.

Despite his known shortcomings as a petty martinet who had his crew walking on eggshells, he did have some things in his favor. Chicago had seen extensive operations in the war so far, as part of a carrier task force and then in the ANZAC Squadron. By all accounts, he handled the ship well at the Battle of the Coral Sea when attacked by numerous enemy aircraft. He was also able to operate effectively as a captain in the Allied squadron with Commonwealth commanders and captains. At Guadalcanal, Chicago served in a new role also, with a fighter controller aboard to direct the F4F Wildcats of the Combat Air Patrol that aircraft carriers covering the operation sent to protect the landing force.

The ship itself was well-armed and equipped, with early warning and fire control radars for her main and secondary batteries, and a new suite of 20mm Oerlikon anti-aircraft guns installed after Coral Sea.

On the other hand, there were some other things he had little control over, such as having to contend with bad lots of 5-inch starshells that would not function and illuminate properly when fired. Although Savo Island would reveal this problem at its worst, it wasn’t an unknown issue, as experienced in various battle practices held by the ANZAC Squadron/TF 44 in between Coral Sea and Guadalcanal.

And at Guadalcanal, he could not control the environment, within the geographic confines of the sound ringed by the islands of Guadalcanal, Tulagi, Florida and Savo. Nor the tempo of combat operations for the first two days of the campaign, very busy between the landings and supply and intermittent Japanese air attacks, with more anticipated. Everyone was exhausted from the tropical environment, the constant general quarters alarms and continuous combat operations.

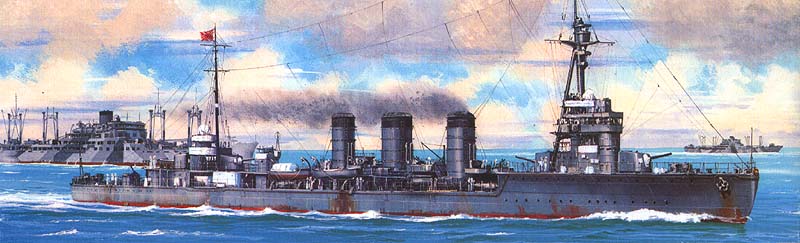

Nor could “King Bode” control the time of day such an opportunity could present itself, or the weather, or one other thing, the enemy. Or in particular, Admiral Gunichi Mikawa, commanding the Japanese task force of five heavy cruisers, two light cruisers and one destroyer rapidly approaching Guadalcanal on his flagship, the heavy cruiser Chokai.

Despite aerial reconnaissance reports of enemy surface ship activity, the details of the reports, and the interpretation of them by various commanders at Guadalcanal generally created a perception of no immediate threat to the landing force at Guadalcanal (one exception would be the commander of the destroyer USS Patterson (DD-392), Lieutenant Commander Frank R. Walker). But the threat was real and imminent as the Japanese cruiser force bore down on the unsuspecting ships of the landing force that night.

Some of that interpretation took place late on August 8, when the commander of the screening force, Rear Admiral Victory Crutchley, Royal Navy, was called to conference and took his flagship out of the southern screening group in order to attend. He turned over command of the two cruisers and two destroyers to Captain Bode.

Bode apparently changed nothing, kept his place in the formation behind heavy cruiser HMAS Canberra instead of assuming the lead of the formation. He issued no orders to the other ships in the southern group, nor the northern or eastern screening groups, which were unaware of the temporary change of command. He may have expected Admiral Crutchley, in command of the screening groups of the landing force to return soon, though the admiral had explicitly stated he might not be back that night.

Things seemed calm and quiet – eventually Bode turned in to his sea cabin to get some rest on that dark night of 8-9 August, exhausted no doubt. It was his bad fortune to be asleep when the Japanese struck, although one wonders whether that would have made any difference, given his lackluster response once awakened at the sound of battle.

Indeed, as Bode came to the bridge the fog and chaos of war took over and he was almost a bystander. Given the unknown threat attacking, he ordered star shells fired, but most did not function and Chicago was deprived of illumination of an enemy target for her guns. Furthermore, an enemy shell struck a leg on Chicago’s foremast killing two men and wounding a number of others, including perhaps the one man who could have helped Bode sort things out. His executive officer was felled by shrapnel in the neck from this shell.

Not only that, Chicago’s forward main battery radar which faced in the direction of the unseen enemy was prevented from functioning properly when a torpedo fired from the Japanese heavy cruiser Kako struck Chicago in the starboard bow.

The shock of the blow and whiplash the ship received bent the small mast atop the foremast in such a way as to prevent the train of the radar. The gun crews tried to acquire a target with their optical sights in the main battery turrets, but without starshell illumination they were unable to detect a target on that dark night.

Robbed of situational awareness, Captain Bode had only the flashes of gunfire to go by. His secondary battery gunners were able to briefly acquire a target and took it under fire, scoring a hit on the Japanese light cruiser Tenryu. But other than that, confusion reigned over King Bode.

And in that moment, as the battle apparently shifted away from the southern group, whose responsibility it was to protect the southwestern flanks of the landing force and the vulnerable troops transports and cargo ships, at that moment, Captain Bode took the hero or goat test, and failed.

He failed to direct the ships of the southern group in battle. He failed to notify the other groups and ships in the landing force about the engagement with a hostile force. And perhaps worst, instead of steaming toward the flashes and sounds of the guns, and interposing Chicago in between the hostiles and the landing force, he ordered Chicago on a westward course, away from the battle area. It was an unfortunate decision for Bode, the other ships in which over 1,000 sailors were to die, as well as to the Marines recently landed on Guadalcanal and Tulagi and soon to be left to their own devices.

With four Allied cruisers sunk in the battle, HMAS Canberra, USS Astoria, USS Quincy and USS Vincennes, the landing force lost its main protection, and later on August 9, departed the area, leaving the Marines on the islands without all of their equipment and supplies yet to be unloaded.

Given the disastrous outcome of this battle, in the first American offensive campaign of the war, the Navy appointed Admiral Arthur J. Hepburn, a former Commander in Chief of the U.S. Fleet, to investigate. He travelled out to the Pacific and interviewed surviving personnel involved, and ultimately wrote a report which identified a number of issues which contributed to the fiasco. But out of all the participants, only one, Howard Bode, was singled out and censured for failure to perform, and that was Howard Bode, identified in the official record as the goat at the Battle of Savo Island.

Some people have suggested Bode was merely a scapegoat, as there was plenty of blame to go around for the failures that terrible night. Indeed, Sandy Shanks wrote a historical novel titled The Bode Testament, published in 2001, which explores this idea at a hypothetical court martial.

Others however, including members of Chicago’s crew, believe the censure was deserved. A sense of shame affected some men, perhaps at the ship’s performance in the battle, and/or survivor’s guilt given the loss of four other heavy cruisers and so many crewmen. But perhaps the shame was more so in the ship’s westward run, away from the battle.

In any event, once Chicago returned to the US for permanent repairs after the battle, Bode was relieved of command, an occasion which was celebrated by many of the ship’s crew, not just for Savo Island but for experiencing all his unpleasant tenure aboard the ship. He was reassigned to shore duty in Panama, to the backwaters of the Pacific War. There he learned of his censure in the Hepburn report, which effectively doomed his career ambitions of making flag rank. Sadly, he took his own life in April, 1943, at 54 years of age.

Chicago’s damage and subsequent repairs in Australia, then in the US, took her out of the war for five months. But fate would bring her back to Guadalcanal and the closing days of the campaign. There she would meet her demise in the Battle of Rennell Island in late January, 1943. Perhaps it was another result, a long-range ripple effect, of the painful reign of King Bode.