USS Chicago was caught up in one of the strangest actions of World War II when Japanese midget submarines attacked Sydney Harbor on the night of May 31, 1942, in what became known as the Battle of Sydney. It showed the mettle of her men, as well as the flaws in her captain. The attack is well-written about in the book titled A Very Rude Awakening by Peter Grose (Allen & Unwin, 2007).

Chicago in Sydney

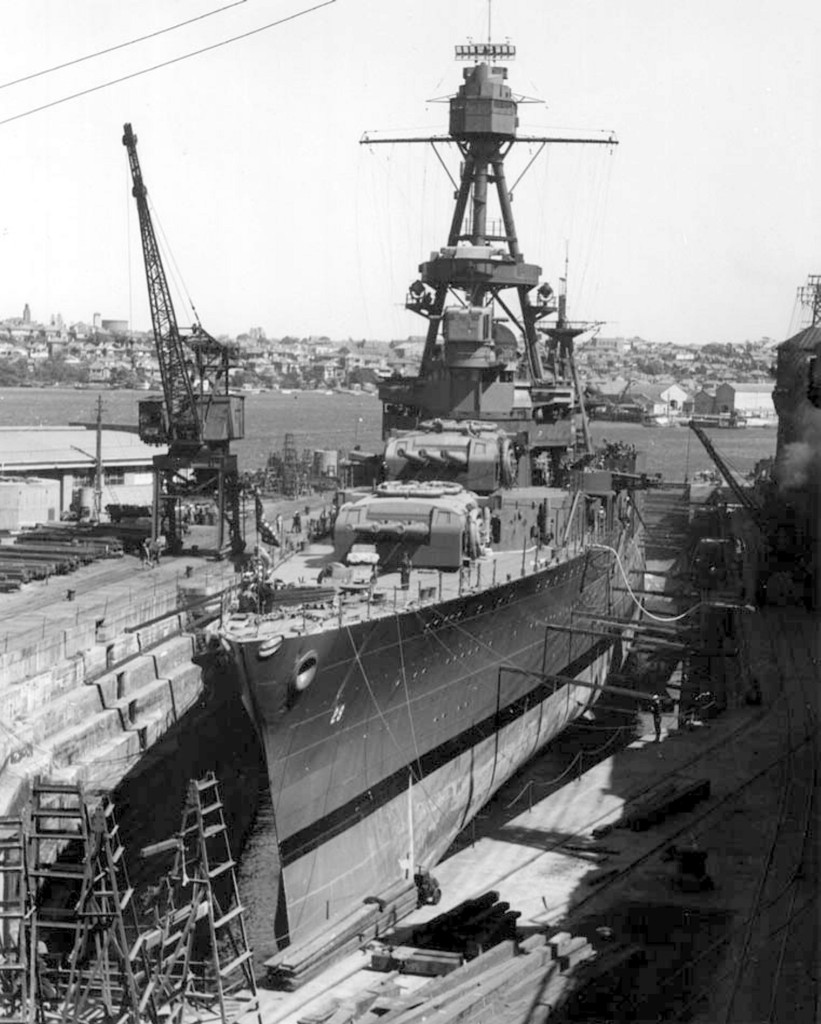

After the Battle of the Coral Sea, Chicago was ordered to Sydney for a brief refit at the Cockatoo Island naval base. She entered the Sutherland drydock at Cockatoo on May 16 and departed on May 25.

Aside from general upkeep, she also received an upgrade in light anti-aircraft armament with the fitting of 11 Oerlikon 20mm cannon to replace her eight 1930s-vintage .50 caliber machine gun in two batteries forward and aft.

While this was going on, members of the crew were permitted liberty in Sydney, a wonderful city and a welcome relief from several months of shipboard duty in the ANZAC Squadron, now designated Task Force 44. Sydney was no stranger to many Chicagomen, who brought the ship to the city in March, 1941, and to Brisbane as well, during the pre-war US Navy goodwill tour in the South Pacific.

But Captain Bode put strict limits on the crew, short reins, wanting them back aboard before midnight after only a few hours ashore. Perhaps he felt it appropriate in a time of war, but he had driven his men hard and some failed to abide in his restrictions. A few of the men returned late and were placed in the brig. But soon the numbers swelled and the additional detainees were placed in the empty flag officer spaces aboard. Such was life aboard Chicago with King Bode.

Japan’s Plans for Sydney Harbor

Danger indeed lurked in wartime Australia, though most people failed to recognize some of them. Warning signs of an impending attack by Imperial Japanese Navy midget submarines revealed themselves one by one, a ship attack, some signal intelligence, and reconnaissance aircraft overflights, but no one was the wiser and it was business as usual in Sydney Harbor, so far from the war.

These small submarines of the Type A Ko-hyoteki carried two 17.7-inch torpedoes and with a two-man crew, and were nearly 80 feet long and displaced about 465 tons. They were propelled by an electric motor which gave them a speed of up to 19 knots underwater. They were carried to a target area by a mother submarine and then launched to make their attack. These midget submarines were a weapon of asymmetric warfare which the IJN hoped would help deplete Allied naval strength. (Note: Although each submarine was given its own unique hull number, for the purpose of simplicity and clarity this post uses an M designation and the number of the mother submarine.)

First used to attack in December, 1941 in the Pearl Harbor attack, the midget submarines of the IJN submarine force planned simultaneous attacks on Allied ports at Sydney (by the Eastern Attack Group), as well as far-flung Diego Suarez harbor at Madagascar (Western Attack Group) off the east coast of Africa. These near-simultaneous attacks were intended to distract Allied forces from the upcoming Midway operation.

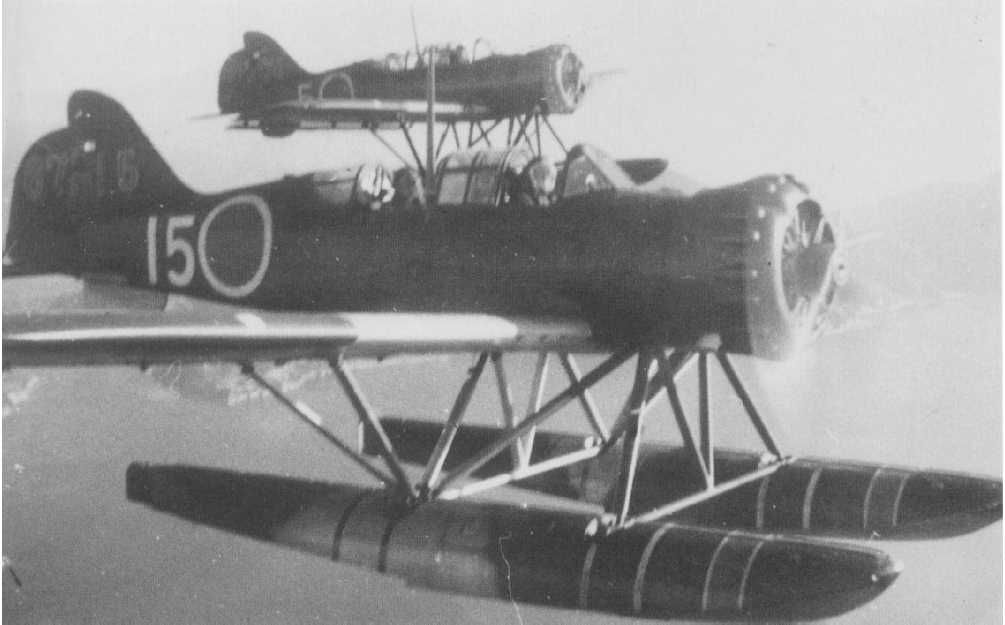

In May, 1942, the IJN deployed its submarines carrying the midgets, and those carrying reconnaissance aircraft, for these attacks. On May 23, the submarine I-29 launched its Yokosuka E14Y floatplane (later codenamed GLEN) on a daytime mission to scout for targets in Sydney Harbor whilst I-21 scouted the harbors at Noumea, New Caledonia, Suva, Fiji and Auckland, New Zealand. The plane was wrecked on its water landing back at the mother submarine, though the crew was rescued. This left I-21 as the only means to conduct a final reconnaissance before the attack.

Despite being detected by radar, the contact was dismissed as a glitch as there were no Allied aircraft operating over Sydney at the time and authorities did not consider the possibility of it being an enemy aircraft. The recon flight confirmed the presence of targets such as two battleships or large cruisers. With a possible British battleship Warspite spotted in the harbor, Sydney was selected as the target for the Eastern Attack Group. (Note: HMS Warspite had been in Sydney between March 20-26, 1942 enroute to the Indian Ocean from the United States after repairs at Puget Sound Navy Yard in Washington State.)

Shortly afterward, the five Japanese submarines of the Eastern Attack Group made a rendezvous some 35 nautical miles northeast of the Sydney Harbor entrance. Three I-boats, I 22, I-24 and I-27, carried a single midget submarine each, while the other two, I-21 and I-29, normally carried a single floatplane, though I-29’s had been wrecked on May 23.

Early on May 29, I-21’s aircraft was used to reconnoiter Sydney again in preparation for the attack two days later, on the night of May 31. The aircraft, with its Japanese hinomaru red rising sun circle markings painted out, flew at a relatively low altitude over the harbor area. Most personnel in the area were complacent. The war seemed so far away, and people who noticed it wishfully thought the aircraft must be an American floatplane from USS Chicago. This despite the fact that Chicago’s floatplanes were biplane Curtiss SOC Seagull types with a single large pontoon, as opposed to the single wing and twin pontoons of the Japanese E14Y floatplane. Only later did some people realize it wasn’t an Allied aircraft.

Despite flying at a low altitude within easy visual observation range, the aircraft was undisturbed on its early morning flight. The Japanese floatplane passed by Chicago, moored just off the east side of Garden Island, twice before returning to its mother submarine, having accomplished a thorough reconnaissance of the harbor.

Since arriving at Sydney in mid-May, Chicago’s gunnery officer had ordered two anti-aircraft guns, one anti-aircraft director and associated crews to keep watch. But two weeks in port must have dulled the sense of urgency, and none of Chicago’s anti-aircraft gun crews apparently noticed the aircraft flying scant hundreds of feet from their ship, though the officer of the deck, an aviator, recognized it as an enemy plane.

Chicago’s gunnery officer, William Floyd, was angry when he learned what happened. He ordered a high state of readiness for the gun and director crews – those on watch had to stand. Only crewmen with an actual sitting role, a gun pointer or trainer, or a director rangefinder, were allowed to sit. He wanted the men to be ready to respond to another Japanese plane, though as things turned out, they were ready for an enemy submarine.

This E14Y aircraft too, was wrecked in landing near its mother submarine, and the crew was rescued. They brought back confirmation that in addition to a cruiser (Chicago) by Garden Island there was another heavy cruiser in port (the Australian heavy cruiser HMAS Canberra). These in addition to other smaller warships and merchant ships and the usual harbor traffic with ferry boats. Sydney Harbor was a lucrative target.

Meanwhile, the Western Attack group struck first at Madagascar, on the night of May 30, and succeeded in putting a torpedo into Royal Navy battleship Ramillies and sinking a tanker. But the British didn’t pass any warning along to other Allies, perhaps unsure whether the attackers were Japanese or Vichy French.

The Battle of Sydney Begins

Came the night of May 31, and Chicago’s captain went ashore for a social engagement, a dinner with the Flag Officer-in Charge of Sydney Harbor, Rear Admiral G. C. Muirhead-Gould. One of Captain Bode’s good points is he apparently got along well with Allies, perhaps a reflection of his earlier diplomatic duty in Europe as a naval attaché. But on this night other events were to reveal his shortcomings.

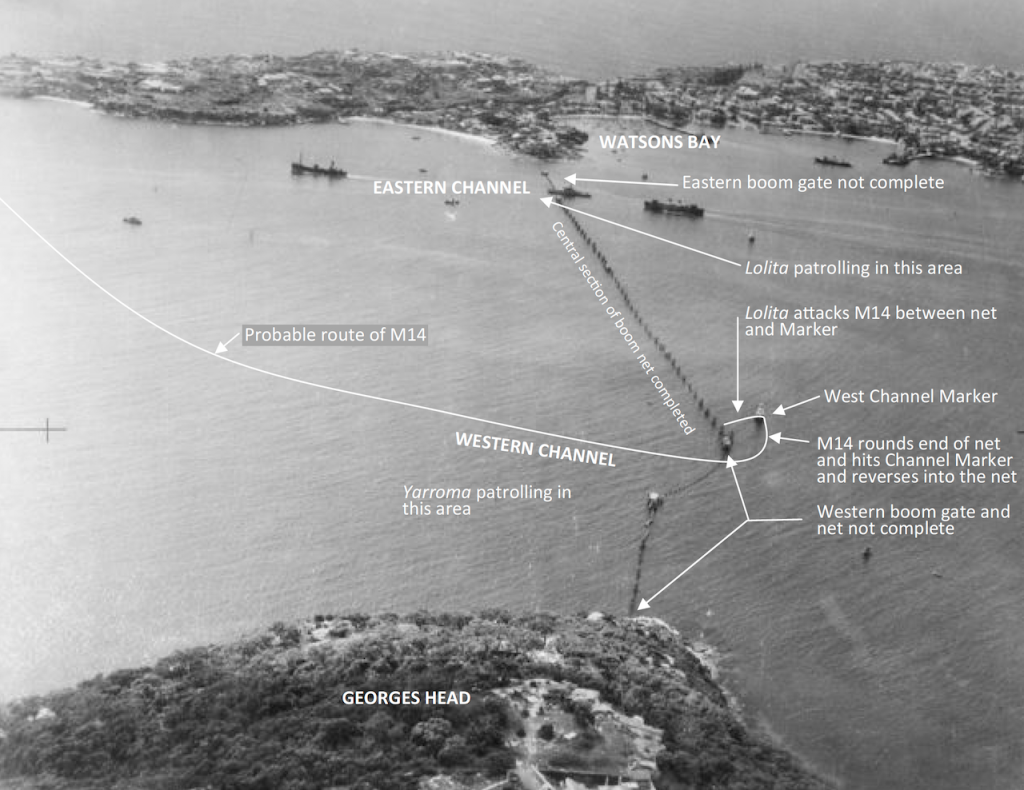

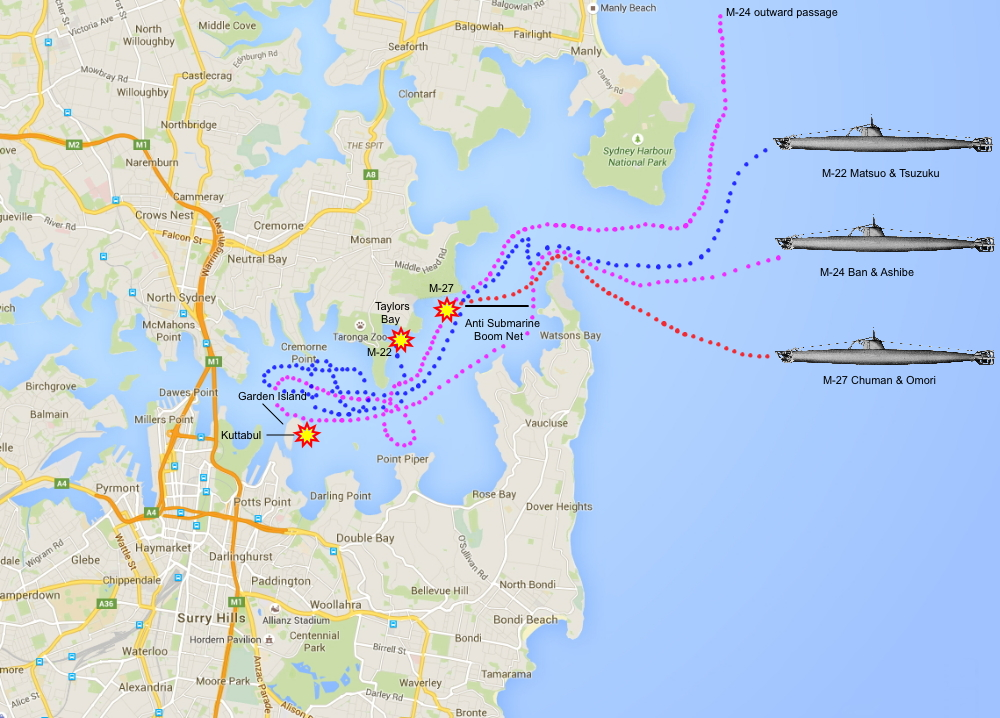

The three Japanese midget mother I-boats, I-27, I-24, and I-22, each launched one midget submarine in that order. The first submarine, M-27, entered Sydney Harbor at about 8pm, but hit an obstacle, backed off and became entangled in an anti-submarine net. As the crew tried in vain to extract themselves, they garnered attention from a couple of patrol boats. Trapped, the crew fired demolition charges at 10:37pm, which caused the harbor to go into an alarm condition.

The second midget, M-24 entered the harbor successfully at 9:48pm and approached the Man-of-War anchorage near Garden Island. It was here that Chicago’s crew began its involvement in the battle.

To sum up Chicago’s role in the battle, at 10:51pm alert lookouts noticed the conning tower of a submarine 300 yards off the starboard quarter. Chicago’s searchlight crews struck an arc, then opened the shutters and illuminated the interloper. The officer of the deck, Ensign Bruce Simons, saw it too and opened fire with his M1911 .45 caliber semi-automatic pistol. General quarters was sounded.

At 10:53pm, a 1.1-inch gun mount near the bridge of the ship opened fire and the gun crew quickly realized it could not depress the guns to bear effectively as the sub was too close. One or two (accounts vary) 5-inch gun crews tried. Depressing their guns as far as they could, they opened fire. But the range was too close again and the shells went above and beyond the sub.

Some of the rounds hit the stone walls of Fort Denison, a small harbor fortification, and others caromed off into north Sydney and amidst shipping in the harbor.

Fortunately there were no friendly casualties and not much damage. Although this did give rise to a radio commenter’s tongue-in-cheek story that one of Chicago’s shells had carried off into Taronga Zoo on the north shore and killed the lion there, and that the Australians hoped a replacement would be sent under the Lend-Lease program.

As the firing began, Chicago was on a four-hour standby for departure, with only one of eight boilers with steam up for supporting the ship’s non-moving needs. However, with pistol shots fired and general quarters sounding, the duty engineering officer, George Chipley, immediately took action to get the ship ready to move, and soon had both engine rooms and the four boiler rooms manned and ready. Lieutenant Commander Herman J. Mecklenburg was the senior officer aboard and took charge. He told the engineering officer to carry on with raising steam and getting the ship ready to go underway. He also signaled USS Perkins, moored nearby at Buoy number 4, to get underway and conduct patrols around Chicago and by 11:15pm, Perkins was underway.

Between the firing and the searchlights the commander of the sub, Sub-lieutenant Katsuhisa Ban, may have realized something was amiss, or he was blinded in the periscope, and/or perhaps he realized he wasn’t at optimum range himself, and the sub submerged. It appeared again about three minutes later, some 300 yards off Chicago’s starboard bow, and the cruiser opened fire again. The Australian corvette HMAS Geelong berthed on the western side of Garden Island also saw the sub and opened fire.

The racket in the harbor drew puzzled responses from military and civilians alike, not yet on to the fact that the harbor had been penetrated by enemy craft. The sound of depth charges exploding at 11:07 pm added to the chaos, as an Australian patrol craft conducted an attack on the third midget sub to enter the harbor, M-22. The sub survived this attack, and waited patiently before moving again after the patrol boat lost contact.

His dinner event ruined by the battle, Chicago’s guns firing and the thumping of depth charges in the distance, Captain Bode returned to Chicago at about 11:30pm in a rage. Commander Mecklenburg tried to tell him what had happened, but Bode was instantly dismissive, accusing his officers of being drunk, insubordinate, jittery fools – there weren’t any periscopes, there weren’t any submarines. He ordered the ship to stand down from General Quarters and to stop all preparations to go to sea. He also ordered destroyer Perkins to cease patrol and return to her mooring.

M-24 attacks Chicago

Bode was still dressing down his officers up on the bridge when M-24 attacked at half past midnight. The midget M-24 fired its two torpedoes at Chicago from aft of the ship; both missed the cruiser, one to port and the second to starboard. Perhaps the steam emanating from Chicago’s smokestacks made the ship appear to be underway and the aim was adjusted incorrectly as Chicago stayed moored at Buoy number 2.

As the torpedoes sped past Chicago, Captain Bode was laying into his officers, telling them how they were to blame for the chaos, fools that got excited over nothing. Bridge personnel saw a torpedo track and warned the captain, but he dismissed it, saying “Hmp! It’s just a motor launch going by.” As he turned to berate his officers again – BOOM! The first torpedo detonated, with an orange flash lighting up the surface accompanied by a huge water geyser.

But Bode’s initial reaction was dismissive yet again,. “There you go, you must have gotten the shore batteries opening up.” Still, a bit of doubt had crept in, and he ordered Commander Mecklenburg to take his gig to Garden Island to make a report and an inquiry as to the cause of the explosion.

The first torpedo that missed Chicago on the port side continued on for 1500 yards and passed beneath the Dutch submarine K9 and the HMAS Kuttabul before striking the Garden Island sea wall and detonating. HMAS Kuttabul, a ferry boat requisitioned as a RAN barracks ship, sank swiftly and 21 Allied sailors were killed, 19 Australian and two British. The other torpedo that missed Chicago ran ashore on Garden Island. M-24 eventually escaped the scene, exited Sydney Harbor and disappeared, at least until it was discovered in 2006 on the bottom of the sea off the coast northeast of Sydney.

By this time with the general alarm in the harbor and an actual attack it was time for ships to evacuate the harbor. Captain Bode reversed his order to cancel preparations to go to sea and by 2:14 am, Chicago advised Garden Island she was ready to depart. Perkins preceded Chicago on the way out of Sydney Harbor, a prudent measure given the presence of the Japanese I-boats in the area. In the hectic departure, a crewman was left on the mooring buoy. And Lt. Cmdr. Mecklenburg chased after the ship in the captain’s gig; the ship slowed and Mecklenburg scrambled aboard.

One wonders if he should have waited, though his return did result in an ironic exchange with Captain Bode, who continued to hector his officers. Chicago was leaving Sydney Harbor as the third midget sub, M-22 re-entered the harbor. Needling Mecklenburg as the ship exited the harbor at 2:56 am, Bode said “You wouldn’t know what a submarine looks like.” To which Mecklenburg responded as he pointed to a midget submarine passing along Chicago’s starboard side “They looked like that, Captain.” Captain Bode finally became a believer, and ordered a message sent to Garden Island “Submarine entering harbor.”

M-22 was later detected in Taylors Bay and subjected to attacks by three Australian patrol boats which damaged the sub, after which the crew killed themselves.

Aftermath

Fortune smiled on Chicago in this battle against the midget subs and Captain Bode. After the excitement of the attack, Chicago briefly returned to Sydney Harbor in the afternoon of June 1 and by evening was out to join the other ships of Task Force 44 and then on her way up Brisbane way. She managed to dodge the five I-boats, which may have been laying low in hopes of a return of the midget subs from Sydney Harbor, but none of the boats returned

No battle star was awarded to Chicago for the Sydney Harbor battle. This writer isn’t clear about what level of fighting is deemed qualified for the recognition with a battle star, but Chicago fought there and the center of attention at the Battle of Sydney, May 31 – June 1, 1942.

Of note, after the battle, the parts of midgets M-27 and M-22 were used to construct a composite vessel, now on display at the Australian War Memorial in Canberra. The conning tower of the M-22 is also on display, at the Naval Heritage Centre on Garden Island, in Sydney Harbor. Sunken M-24 is protected as a war grave.

When Chicago returned to Sydney some three months later for battle damage repairs after the ignominious Battle of Savo Island, Captain Bode was presented with the net cutter from one of the midget submarines. One wonders how the crew felt about this memento. But there would be no trophy for his performance at Savo Island.

References

A Very Rude Awakening, Peter Grose, Allen & Unwin, Sydney, 2007

Perryman, John, “Japanese Midget Submarine Attack on Sydney Harbour,” at: https://www.navy.gov.au/history/feature-histories/japanese-midget-submarine-attack-sydney-harbour

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Attack_on_Sydney_Harbour

USS Chicago War Diary for May, 1942 and Action against enemy submarines, May 31, 1942 – report of (June 5, 1942)